Scientists To Bid A Bittersweet Farewell To Rosetta, The Comet Chaser

An illustration of Rosetta just before Friday’s expected landing on the comet known as 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The final approach aims to be only at “walking speed,” mission specialists say, but that’s enough to tip the antenna away from Earth.

ATG medialab/ESA

hide caption

toggle caption

ATG medialab/ESA

An illustration of Rosetta just before Friday’s expected landing on the comet known as 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The final approach aims to be only at “walking speed,” mission specialists say, but that’s enough to tip the antenna away from Earth.

ATG medialab/ESA

On Friday, the Rosetta spacecraft will smack into the icy surface of the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and go silent. Scientists with the historic mission are wondering how they’ll feel as the orbiter makes its death-dive toward the comet that’s been its traveling companion for more than two years.

“There’s mixed emotions here,” says Matt Taylor of the European Space Agency, who is the project scientist for Rosetta. “You know, people have invested their lives and their mentality, I think, as well — their psychology — on this mission. I really couldn’t tell you what I’m going to feel.”

Mission controllers in Darmstadt, Germany, will command the spacecraft to do a specific maneuver on Thursday evening that will put it on a collision course with the comet. “From that point,” Taylor says, “it’s free fall, effectively.”

The whole way down, the spacecraft will be collecting data and images that it will stream back to Earth in real time.

“And as soon as any one part of that spacecraft touches the comet, it will tilt the spacecraft,” Taylor says. “The antenna won’t be pointing at the Earth, and we lose the signal. We’ll know that it’s impacted when we can’t hear from it anymore.”

The finale will send Rosetta down to explore an interesting region of the comet that has big pits. The walls of these pits seem to have a bumpy, almost lizard-skin texture, says Taylor, who notes that the goose-bump-like features are a few feet across.

Rossetta’s mission control specialists at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany, were jubilant on Jan. 20, 2014, after getting back the first signals that their mission’s probe had “woken up” on the comet’s surface .

Juergen Mai/ESA

hide caption

toggle caption

Juergen Mai/ESA

Rossetta’s mission control specialists at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany, were jubilant on Jan. 20, 2014, after getting back the first signals that their mission’s probe had “woken up” on the comet’s surface .

Juergen Mai/ESA

“We think they’re fundamentally important in the make-up of the comet,” Taylor says. “Those bumps potentially are the building blocks from which the larger-scale comet is made.”

To get high-resolution images of those features in the walls of the pits, “would be fantastic,” he says.

Rosetta left Earth in 2004 and trekked through space for a decade before reaching comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in August 2014 and slipping into orbit.

Orbiting a comet was a major first for science; the mission achieved another unprecedented success a few months later, when Rosetta deployed a small probe that touched down on the comet’s surface.

Unfortunately, anchors on the probe failed and it bounced a couple times before finally coming to rest in a shadowy crevice. The probe, called Philae, lasted only a few days after that, because its solar panels couldn’t get enough sunlight to recharge its batteries. Still, researchers were still able to retrieve valuable images and information.

ESA only recently figured out exactly where Philae ended up, and Rosetta will be laid to rest not too far away, on the “head” of the comet that’s shaped like a rubber duck.

The time Rosetta spent orbiting this comet has given scientists an unprecedented opportunity to watch one of these icy bodies in detail as it approaches the sun. Most previous comet missions only flew past a comet (one spacecraft, Deep Impact, deliberately collided with a comet), which meant that scientists could only retrieve data for a few hours or days.

Planning for the mission began all the way back in the 1980s, says Taylor.

“You’re looking at over 30 years to get you to a science target. It takes time and effort,” he says. “There are scientists and engineers who have spent their lifetime working on this mission.”

Comets interest scientists because these complicated icebergs could shed light on our solar system’s beginnings. “Comets are the best preserved samples of solar system material from the origin,” says Paul Weissman, a scientist with the Rosetta mission at the Planetary Science Institute. “They’ve been totally unmodified since 4.5 billion years ago, when the planets and the sun formed.”

He says Rosetta has already turned up a lot of surprises. For example, researchers previously thought comets had only small, active areas on the surface that spewed jets of dust and gas.

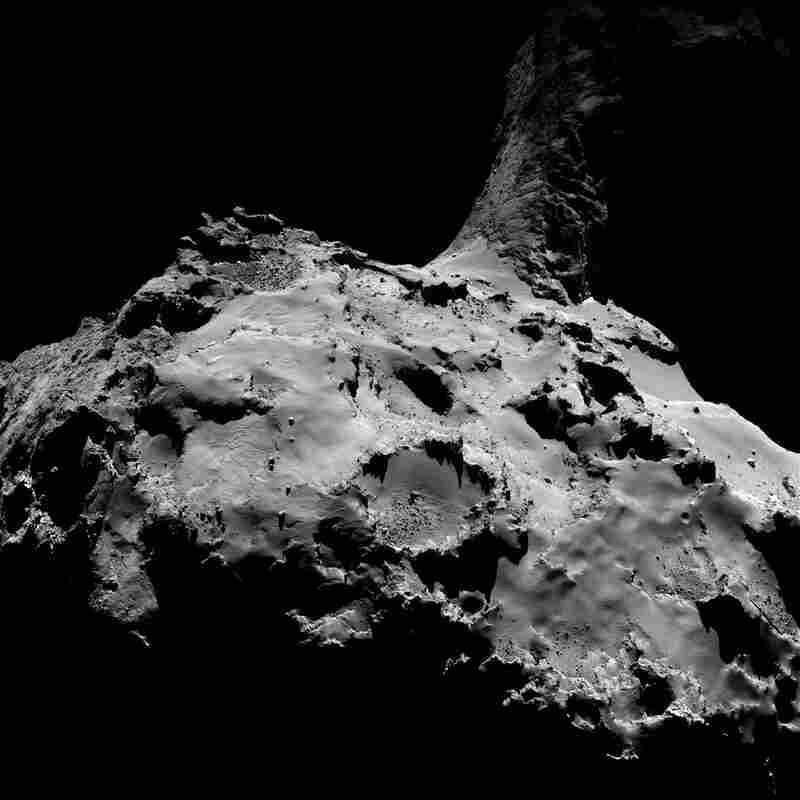

Rosetta was 13.3 km from the nucleus of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, when it took this wide-angle image on July 4. Thanks to Rosetta, scientists now know a comet’s entire surface can spew dust and gas.

Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team/ESA

hide caption

toggle caption

Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team/ESA

Rosetta was 13.3 km from the nucleus of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, when it took this wide-angle image on July 4. Thanks to Rosetta, scientists now know a comet’s entire surface can spew dust and gas.

Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team/ESA

“It turns out, almost all of the surface is active,” Weissman says, “but it’s active at a very low level. So it’s a very different mechanism than what we previously thought. This is going to send everybody back to the drawing boards to understand how this mechanism works.”

When Rosetta finally hits the comet’s surface, it will be going slow enough that its “controlled landing” isn’t likely to destroy it, even though it won’t be able to talk to Earth.

“It will only hit at about a meter per second — which is walking speed,” Weissman says. “So imagine yourself walking into a wall, at just walking speed. It wouldn’t damage you very much.”

Scientists will continue to analyze the data gathered by Rosetta for years to come. Meanwhile, the spacecraft and its lander will continue their journey, riding on the comet’s surface indefinitely.

“They will stay where they are, as best we can expect,” says Weissman. The comet should travel that way through the inner solar system for the next half-million years, he says, only to be ejected by Jupiter, eventually, to a much more distant orbit.