Busy coffee shops and bank machines top list of ideal spots to place life-saving devices

Every second counts when someone is having a cardiac arrest — but there’s often a disconnect between where the event happens and the nearest defibrillator. New research focusing on Toronto suggests that busy coffee shops and bank machines may be ideal locations for the life-saving devices.

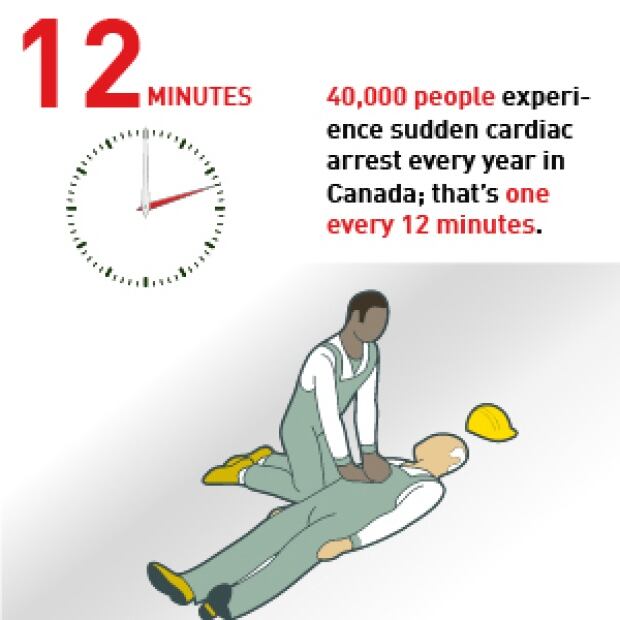

When a cardiac arrest occurs, the survival rate decreases by 10 per cent for every minute that CPR and application of a defibrillator is delayed, emergency room doctors say.

- Defibrillator-equipped drones could be 1st on scene in cardiac arrest

- Defibrillators may be hard to find in emergencies: CBC investigation

Until now, physicians, governments and community efforts have focused on placing automated external defibrillators or AEDs in shopping malls or office buildings so bystanders are able to access the devices to help when someone’s heart malfunctions electrically and stops beating.

But previous Canadian research suggests about one in five cardiac arrests happened when a nearby defibrillator was in a location that was closed at the time, said Prof. Timothy Chan, director of the Centre for Healthcare Engineering at the University of Toronto.

When someone experiences a heart attack, access to a defibrillator can mean the difference between life and death. (CBC)

Chan and his colleagues created two overlapping sets of Toronto maps to show where cardiac arrests occurred from 2007 through 2015 in relation to businesses with defibrillators, taking into account the business hours at each location. The researchers used information from paramedics, the Canadian Franchise Association, websites and in some cases personally visited locations to confirm the working hours.

The rankings were based on where cardiac arrests were the most frequent and where defibrillators were available when needed.

Coffee shops (Tim Hortons, Starbucks and Second Cup) and automated bank machines of the five major Canadian banks topped the list of where defibrillators should be located, published in Monday’s issue of the journal Circulation.

Tim Hortons was ranked first, with more than 300 shops in Toronto. The researchers estimated these locations alone would have provided AED coverage for more than 200 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests over an eight-year period.

What’s more, the rankings were stable over time, Chan said.

Favourite haunts

The number of AEDs alone won’t improve outcomes for patients, previous research suggests. Knowing where they are is key.

“Most people probably don’t know where necessarily the closest AED is to them at any given point,” Chan said in an interview. “But you can probably have a rough idea where the closest Tim Horton’s is, or where your ATM is because you might frequent that ATM a lot.”

- App could save lives by connecting people having heart attack to help nearby, paramedics say

Creating a mental link between AED and these places you’re familiar with is “so powerful in helping activate people to respond,” he said.

The study’s authors also found that ABMs, which are often standalone and outdoors and available 24/7, also ranked well. The ABMS also featured security cameras and protection from the elements and were broadly recognizable.

Green P public parking lots also made the list.

Prof. Timothy Chan hopes his rankings of businesses will guide public placement of AEDs. (American Heart Association)

In total, there were 27,650 cardiac arrests in the city over the study period, of which 2,654 occurred in public.

Cardiac arrests are a life and death situation, said study co-author Dr. Steven Brooks, an emergency physician in Kingston, Ont. Even if AEDs are well placed, it doesn’t mean they’ll be used in an emergency.

“We have to start thinking beyond the traditional approach of simply placing them, hanging a sign and then crossing our fingers, hoping that they will be used when the time comes,” Brooks said.

There are opportunities to use innovative strategies, such as drone-delivered AEDs and crowdsourced apps to bring members of the public, AED locations and their delivery together with 911 dispatch services. The goal is to get CPR and AED to every victim of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest within two minutes of their collapse, Brooks said.

Better survival

Brooks, who also works on drone delivery of AEDs in residential and rural areas, envisions these approaches coming together, perhaps alongside miniaturization of AED technology so that mobile devices could be used to defibrillate.

“Once all of these pieces of the puzzle come together, I predict that we will see a drastic increase in the number of people surviving out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” Brooks said.

A journal editorial accompanying the study praised how the research marries expertise in emergency medicine, mechanical and industrial engineering to inform public policy with a method that could be applied to other cities.

But whether systemically deploying AEDs at high-ranking businesses in fact increases rates of bystander AED and survival still needs to be tested.

To apply the findings, businesses, governments and advocacy groups such as Heart Stroke and defibrillator suppliers will likely need to come together, Chan acknowledged.

Chan expects coffee chains and banks will be open to participating for charity and to promote good will while enhancing their brand.