British researchers lost a genetically modified mouse and accidentally released a smallpox-like pathogen in a series of biosecurity blunders kept secret.

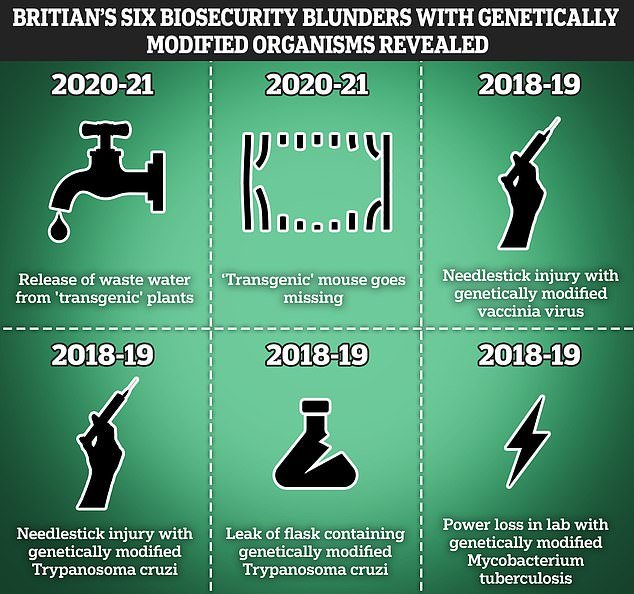

Six laboratory incidents where genetically modified organisms (GMO) have escaped containment in the past five years.

Four occurred before Covid took over the world.

Research into genetically modified pathogens has come under intense pressure since the pandemic broke out, with some believing Covid emerged from similar, controversial experiments.

It has led to calls for stricter regulations on studies that deliberately modify viruses and bacteria.

MailOnline has learned of six laboratory incidents where genetically modified organisms (GMO) have escaped containment in the past five years. Four occurred before Covid took over the world

None of the incidents revealed on this website posed a high risk, leading experts stressed.

However, biologist Dr. Richard Ebright, an outspoken critic of so-called gain of function experiments, argued that such accidents are more common than we think.

He told MailOnline: ‘Laboratory accidents involving pathogens, including genetically modified pathogens, are an almost daily occurrence worldwide and occur even in the best of circumstances.

“The world needs more oversight and regulation of this type of research.”

All the incidents – which only date back to 2018 – were discovered through a Freedom of Information request.

One involved a genetically modified type of mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis.

The government’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE) cited the cause of the accident as a power failure while scientists worked with the bacteria.

The report does not say how many people may have been exposed, for how long, or how the outage occurred in the first place.

Tuberculosis – often considered a Victorian-era disease – still kills 1.5 million people worldwide every year. It is mainly spread through coughing.

Two other incidents involved genetically modified versions of trypanosoma cruzi, a microscopic parasite that causes Chagas disease.

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is potentially fatal if left untreated and normally spreads through insect bites.

In the first incident, which took place in 2018/19, a laboratory worker accidentally injected himself with the parasite.

The second involved a leak in a container containing the parasite.

No other details have been released.

Both mycobacterium tuberculosis and trypanosoma cruzi are classified as ‘Group 3’ pathogens by HSE in the UK for research purposes.

In practice, this means that they have the potential to ’cause serious illness in humans and could pose a serious hazard to workers’.

This classification recognizes that there is a risk that such pathogens could ‘spread to the community’ in the event of an accident.

By comparison, the Ebola virus is classified as ‘Group 4’ – the highest possible grade for research regulation.

Another incident involved a vaccinia virus, which is closely related to smallpox – an infectious disease that was eradicated in the 1980s thanks to a global immunization campaign.

Two other incidents involved genetically modified versions of trypanosoma cruzi, a microscopic parasite that causes Chagas disease. Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is potentially fatal if left untreated and normally spreads through insect bites. In the first incident, which took place in 2018/19, a laboratory worker accidentally injected himself with the parasite (stock)

Similar to one of the trypanosoma cruzi incidents, a laboratory worker accidentally stabbed himself with a syringe containing the virus in 2018-2019.

Vaccinia virus is classified as a group 2 pathogen in Britain, making the risk one step lower than Mycobacterium tuberculosis and trypanosoma cruzi.

Two other accidents involving genetic modification research were recorded in 2020-2021.

One involved a genetically modified mouse that went “disappeared,” meaning it went missing.

The information does not reveal exactly what study the mouse was used for.

However, it was classified by the HSE as ‘non-notifiable’, meaning it should in theory fall on the lower risk scale to the public.

The latest incident involved an ‘unintentional discharge of wastewater’ during research into genetically modified plants.

Data about the incidents does not reveal the purpose of the research scientists conducted.

Dr. Ebright of Rutgers University said the accidents did not involve pathogens likely to cause another pandemic.

He mentioned pathogens such as bird flu, coronaviruses such as SARS and MERS, smallpox and the pathogens behind diseases such as Ebola.

Although information about laboratory accidents is not regularly published by law, those running the laboratories must report incidents to HSE.

Laboratories wishing to modify organisms must notify the HSE watchdog of any accidents that occur in the process.

Dr. Filippa Lentzos, a biosecurity expert at King’s College Londonand part of Global Biolabs, a team of experts who monitor laboratories studying pathogens around the world, said the accidents appeared to be at the lower end of the risk scale.

However, she told MailOnline that a true assessment of the risk would require more details about exactly what scientists were modifying the pathogens for.

Dr. Lentzos also emphasized that the fact that these accidents were publicly recorded at all was a credit to laboratory transparency in Britain.

Other countries may be much more secretive with similar research.

“The UK and other European countries with similar regulations are much more transparent about biosafety than most countries globally, so this kind of public reporting should be recognised, appreciated and encouraged,” she said.

‘Reporting incidents in this way is important to reduce the chance of these types of accidents happening again.’

An HSE spokesperson said: ‘A laboratory wishing to undertake activities with genetically modified organisms (GMOs) would have to comply with the requirements of various legal frameworks which are closely regulated by ourselves.’

There is a huge debate among experts about what exactly constitutes gain of function research.

Some studies are not designed to deliberately create a more dangerous pathogen, but may do so while modifying it to learn more about how it infects cells.